US government debt is a ticking time bomb

The predicament doesn’t have to end in crisis. But, since that’s the way it appears to be headed, Stéphane has taken a look at the risks and what you can do to protect your portfolio.

31st May 2024 09:14

- The US debt load is on an unsustainable path: interest rate costs are rising faster than the government’s ability to pay them, there’s no credible plan to balance the books, and investors’ confidence has started to erode.

- Spiking US yields could escalate the debt crisis, and heighten fears of inflation and currency devaluation.

- Gold, bitcoin, and real assets may help make your portfolio more robust as those risks rise.

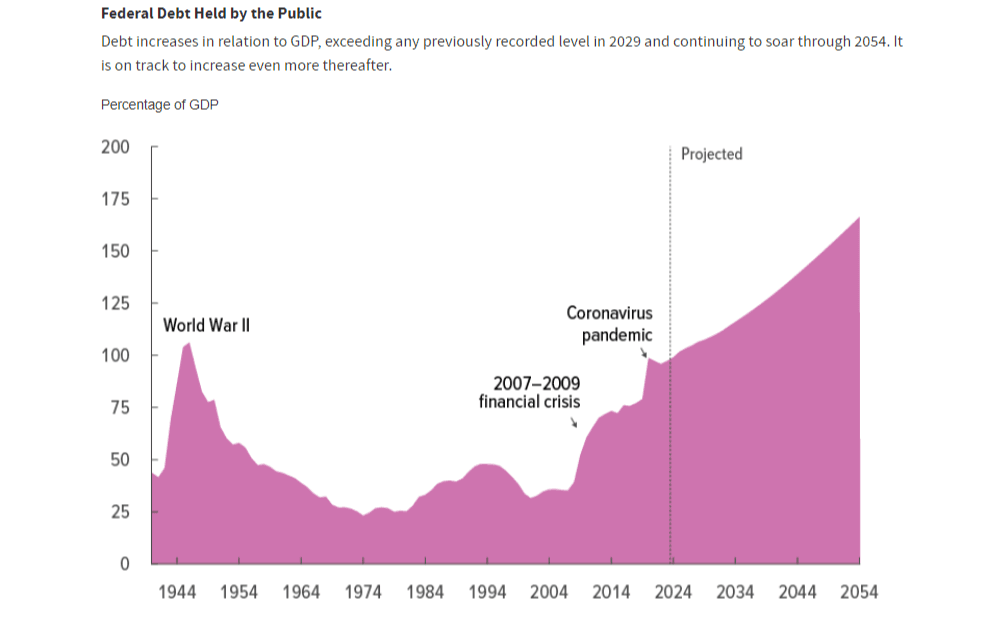

If it seems like the US debt load is, ahem, weighing on some people’s minds more than ever, there’s a pretty good reason for that. The amount the country owes, relative to the size of its enormous economy, has never been so big, outside of wartime. It wasn’t such a worry when interest rates were ultra-low, but with today’s higher rates, the risks are rising – and that’s not just because of the increased costs of repaying all that debt.

The amount of US debt held by the general public as a percentage of the size of the overall value of the goods and services produced by the economy in a given year – a measurement typically referred to as debt-to-gross-domestic-product, or debt-to-GDP. Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Isn’t a high level of government debt always risky?

Not necessarily. As long as the debt burden remains bearable and future spending remains under control, governments can manage some pretty significant debt levels.

Four factors can help determine how sustainable the debt level is: the size of the government budget deficit (that is, how much it spends beyond what it earns), its economic growth (the stronger it is, the easier it will be to pay off debt), its real interest rates (low levels will reduce the cost of servicing that debt), and the confidence in the country’s leadership (which can allow policymakers to borrow and roll over existing debt at favorable terms). These factors ensure the government can refinance its debt affordably and keep its spending priorities in place without creating instability.

But, even if a country meets all those criteria and technically has sustainable debt, that doesn’t mean things will be easy. Higher debt levels mean that even a small change in interest rates can seriously alter the cost of managing that debt. When an economic slump or an urgent spending need arises, a government’s ability to respond can be dramatically restricted. Plus, as the debt rises, relative to the size of the economy, it boosts borrowing costs for the private sector and forces the government to compete with it for funds, crowding out private investment and stifling economic growth.

Making matters worse, sky-high debt just has a way of spooking the market, making it pricier and trickier for the government to borrow more down the line.

So, yes, there are negative consequences to having high levels of debt, even if the load is technically sustainable and doesn’t pose the risk of a crisis.

So then, why are these folks so worried?

Right, well, the problem is, the US debt doesn’t appear to be sustainable.

Sure, it’s got some powerful factors playing in its favor: the dollar’s status as the global reserve currency and the depth of US financial markets both help keep the country’s borrowing costs low. And the Federal Reserve has a huge capacity to buy up government bonds through “quantitative easing” programs, and that can also help contain interest rates. Plus, the US economy is strong, and AI has the potential to make it even stronger. And then there’s the most supportive factor of all: its debt is issued in its own currency, meaning it can always “print money” to pay it off, reducing the risk of a catastrophic Argentinian-style default.

But the cracks are starting to show. The US now spends more on interest than it does on national defense. The country has a growing budget deficit and no clear plan to shrink it. And, to be fair, it wouldn’t be easy to do so if it tried: just to keep that debt-to-economy ratio (or debt-to-GDP ratio) stable for the next 30 years, the US would need permanent spending cuts or yearly tax increases totalling 2.37% of the value of the entire economy starting in 2025 – about $668 billion in today’s money, or 27% of current income tax revenues. That doesn’t even factor in risks like inflation volatility, a changing macro environment, fiscal deficits, and central bank moves, all of which could push interest rates higher.

In fact, if interest rates were to stay above economic growth, debt-to-GDP would soar. And with the cost of servicing the debt rising faster than the government’s ability to pay, policymakers would probably have to create more debt just to cover interest payments, leading to an escalating debt cycle. And that would happen at a particularly concerning moment – right when investor confidence in US government and central bank policies has started to falter.

That last point may be the most important. As economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff have warned, debt is fundamentally all about investor confidence. When investors doubt a borrower’s ability or willingness to repay a debt in full, that can trigger a debt spiral. It begins as waning confidence prompts lenders to demand higher interest rates, pushing borrowing costs higher, increasing debt servicing expenses, and necessitating more borrowing – which, in turn, escalates debt levels. This further erodes confidence, perpetuating the cycle and making the debt crisis go quickly from bad to worse.

In extreme scenarios, this kind of thing could trigger a full-blown financial crisis. Sharp spikes in Treasury yields could send the value of government bonds lower (because their prices fall as their yields rise). Banks, insurers, and funds holding these securities – in other words: everyone – could face painful losses, potentially leading to collapses. And, given the US’s global influence, this chaos could spread worldwide.

So, is a crisis inevitable then?

Not for now, but the risks are rising. Look, the government’s debt doesn’t have to be completely paid off, but it would be good to shrink it to manageable levels.

And there are at least four things that could help make that happen. First is austerity measures: basically cutting government spending and increasing taxes to trim the size of the yearly budget deficit. Second is strong economic growth, which helps boost the overall size of the economy, making the debt smaller on a relative basis. Third is debt monetisation, which entails essentially “printing money” to buy government bonds, which weighs down borrowing costs and adds liquidity to the economy. And fourth is financial repression, where policymakers do things like mandating that banks hold government debt, capping interest rates, restricting foreign flows, and favoring government borrowing – all of which can diminish the real value of the debt over time (though often at the expense of savers and investors).

The first option seems unlikely: politicians have little incentive to balance the fiscal budget. What’s more, factors like climate change, geopolitical risks, deteriorating infrastructure, and a polarised electorate suggest an even wider deficit may be on the horizon.

Strong economic growth is more probable, helped by AI-driven productivity gains, but it’s risky to bet on such an uncertain outcome. So that increases the likelihood that debt monetisation and financial repression will be the go-to tools. The methods are risky, though: they could send inflation spiralling out of control, devalue the currency, distort financial markets, and ultimately impact long-term growth.

And, sure it’s possible to achieve a “beautiful deleveraging” – where debt is reduced to a manageable level while growth and inflation remain reasonably sturdy – but doing so requires just the right mix of factors and is very difficult to achieve. It’s why major debt issues have ended in crisis, more often than not.

Unfortunately, it seems unlikely that the US government will make a serious attempt to solve the issue before a major accident – like seeing Social Security or Medicare run out of cash in the early 2030s. If interest rates remain higher for longer, if inflation rises again, or if the economy experiences a big slowdown, confidence could evaporate much earlier than that.

So, what should you do then?

Thing is, timing any crisis is extremely difficult – and that goes for debt crises too. As German economist Rudi Dornbusch noted: “Crises take a much longer time coming than you think, and then happen much faster than you would have thought”.

Sure, you can wait for the market to tell you when it’s nearing a critical point. Keeping tabs on the performance of “devaluation” assets like gold and bitcoin, along with indicators like the term-premia (the added compensation investors require to hold longer-dated government debt), inflation expectations, the cost of insuring against a US default, US dollar trends, and interventions by the Fed and the Treasury in bonds and money markets might all provide useful signposts. But here’s the kicker: you’re unlikely to have a clear signal until it’s too late.

The prudent move, then, might be to own assets that could do well even if a US debt crisis strikes, potentially bringing inflation and currency devaluation along for the ride. For me, gold shines as the top pick here: it’s historically held its ground in similar scenarios and remains under-owned – roughly two-thirds of advisers have little to no exposure to the metal. Bitcoin might also serve as a useful hedge, it’s got a spottier track record and a riskier profile and tends to behave more like a speculative asset. So make sure the size of your position reflects that.

Don’t overlook real assets, since real estate and commodities are likely to preserve their value in most rocky scenarios. And don’t feel you need to shed your stocks: they may be volatile, but they’re still likely to outperform cash in real terms over the long term. Instead, make sure your portfolio is well-diversified geographically. And remember, the ride could get bumpy. So, it’s crucial to have a solid game plan that plots out how you’ll stick to your strategy through the ups and downs, and how you’ll capitalise on opportunities that pop up.

Stéphane Renevier is a global markets analyst at finimize.

ii and finimize are both part of abrdn.

finimize is a newsletter, app and community providing investing insights for individual investors.

abrdn is a global investment company that helps customers plan, save and invest for their future.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Editor's Picks