One common hedge-fund trade could bring down financial systems – and it nearly backfired this week

The ‘basis trade’ should be a relatively risk-free way to lock in a small and steady profit. And if you’re a big-buck hedge fund, you can turn that into millions.

11th April 2025 11:45

Russell Burns from Finimize

- The loss of safe-haven status for US assets (like bonds and US dollars) was an unwanted effect of the US president’s radical trade policies

- Hedge funds use the “basis trade” to profit from the price differences between Treasury bond futures and cash bonds, typically using hundreds of millions worth of borrowed cash to increase their returns

- If market conditions had deteriorated much further, hedge funds could have faced significant losses, forcing them to wind down trades – which could have further destabilized broader financial markets.

Investors didn’t just run from stocks when the tariffs got tough. They dipped out of bonds, too – which may come as a shock, given that the assets tend to be hailed as “safe havens”. And all of this kerfuffle has put “the basis trade” in the spotlight: a hedge fund favorite, the strategy is hailed as a “risk-free” way to lock in profit. Well, clearly not. Let’s see what can go wrong with this huge and common hedge fund trade, how that could derail the broader system, and why we avoided the fallout this time.

What’s the basis trade?

Let’s say you’re keeping an eye on the price of future contracts in the bond market. Remember, futures are an agreement to buy or sell an asset at a fixed time or price later on. You notice that a bond today costs less than what the future contract says it should cost in the future. (Maybe futures are in especially high demand, or more bonds recently entered the market.) By buying a bond and selling the future today, you could pocket the difference down the line.

So imagine a real bond costs $99 today. You sell a future that binds you to deliver a bond at $100 down the line. (The price differences tend to be quite tiny.) Fast forward to the expiry date, and you deliver your $99 bond and pocket the $1 difference.

Now, that’s hardly life-changing money. So when hedge funds do this trade, they use hundreds of millions of US dollars to make it worthwhile. They don’t rely on their own wallets, mind you. Hedge funds hit up repo markets – essentially pawn shops for traders – to borrow most of the purchase price, using the bonds as collateral. We’re talking serious leverage here: to buy $500 million worth of bonds, they might front as little as $10 million on their own. While they wait to settle the trade, they pay interest on the loan. And if prices start moving in the wrong direction, hedge funds can limit their losses by selling the bond and closing out the future.

In theory, it’s a risk-free way to exploit a price gap for profit. In reality, that’s not always the case.

What could go wrong?

For these trades to work, hedge funds need the right conditions. That means a smoothly running repo market for easy access to leverage, plenty of available cash in both bonds and futures markets so they can easily enter and close positions, and low repo rates to ensure that the cost of borrowing doesn’t wipe out their profit.

Problem is, the rates offered by repo markets can quickly pick up. That could happen for a few reasons – to name some: Federal Reserve policy changes, a sudden demand for cash from financial institutions, foreign central banks selling Treasuries at the same time, or a sharp rise in credit risk.

And when those repo rates rise, hedge funds need to keep up with their increased borrowing costs. At best, that slims their margins. At worst, it makes the trade completely unprofitable. When hedge funds end up hemorrhaging money as a result of sudden spikes in interest rates, they have little choice but to wind down their positions – fast. Other investors then sense panic in the air – or well, the bond markets. They often unload their own Treasuries in response, shrinking the pool of buyers and exacerbating the problem.

In a worst-case scenario, hedge funds could buckle under the pressure, with their struggles rippling through the broader financial system.

This scenario isn’t hypothetical: it was narrowly avoided during the pandemic, when a spike in repo rates forced funds to unwind their basis trades, thanks to emergency intervention from the Federal Reserve. History is full of similar examples, demonstrating how overreliance on certain rates and circumstances can lead to widespread panic and selloffs – and from there, breakdowns across the financial system.

What happened this time?

The US president’s escalating tariffs rattled investors, companies, and governments around the globe. Before the pause in levies was announced, investors had fled from a whole host of stocks, sending major markets toward the floor. The US dollar and American bonds tend to be popular picks during volatility – often referred to as “safe havens” because they usually hold their value. But not this time…

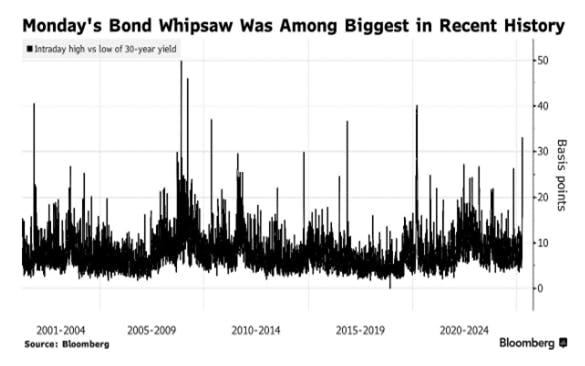

On 7 April, bonds moved around more during the trading day than at any time in the last five years. On 9 April, the yield (the returns investors get paid) on 30-year Treasuries briefly poked above 5% for the first time since November 2023, posting the biggest three-day increase since 1982.

US 30-year bond intraday high versus low from 2000 to 2025. Source: Bloomberg.

That’s lit a fire under the MOVE index – which tracks volatility in US Treasury bonds – to levels not seen since March 2023.

Implied volatility for US bonds and stocks from 2023 to 2025. Source: Bloomberg.

The US dollar also slid against other major currencies.

Now, one of the US president’s goals was to reduce interest rates. That would make borrowing cheaper – mortgages would be more affordable for Americans, investment easier for businesses, and debt repayments more manageable for the US government. What seems to be the loss of a safe-haven status for bonds and greenbacks is an unintended consequence of these new radical economic policies.

Bond traders seemed to have kept the US president in check, though. There’s talk that hedge funds liquidated their basis trades at a rapid pace in response to tariffs. It’s also rumored that Japan and China, the two biggest holders of US Treasuries, ditched some of their holdings. Other investors shifted to shorter-term bonds, which are less at risk of being impacted by stagflation (a slow economy and high inflation).

As I said earlier, this sort of mass exodus from bonds could spread across the wider financial system. And yes, the US president said he would be willing to risk a recession to reshape global trade – but when money markets and broader funding look set to break, you’re now looking at potentially irreversible damage to the economy. The warning was heeded: the president granted most countries a 90-day delay before additional tariffs start.

Investors celebrated hard by sending stock markets higher at record speeds, while the US dollar and bond markets only rallied a little. But the precedent has been set: no one can predict the next few days – let alone months – of policy nowadays. So investors are still nervous, with negotiations still to be had and China’s tariffs still well above 100%. But with the president seemingly eager to keep bond yields from moving too high, longer-dated bonds may look a little more attractive again.

Russell Burns is an analyst at finimize.

ii and finimize are both part of abrdn.

finimize is a newsletter, app and community providing investing insights for individual investors.

abrdn is a global investment company that helps customers plan, save and invest for their future.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Editor's Picks