HMRC tax raid hits savers: tips to protect your income

A combination of higher interest rates and frozen tax allowances is pushing more savers into paying tax. Craig Rickman explains what you need to know and suggests ways to keep the taxman at bay.

14th November 2023 15:44

Higher returns on cash savings have been a bright spot of the most aggressive interest rate hiking cycle in modern history. If you shop around, you can now earn more than 5% a year for the first time since the late 2000s.

But a consequence of higher savings rates is, of course, larger tax bills. The Financial Times reported last week that savings interest tax collected by the government is expected to swell from £3.4 billion in 2022 to £6.6 billion this year, according to figures from HMRC. What’s more, an extra one million people are set to pay tax on savings interest this year – a looming administrative headache for both the savers concerned and the UK’s tax authority.

- Our Services: SIPP Account | Stocks & Shares ISA | See all Investment Accounts

However, from the personal savings allowance to cash individual savings accounts (ISA), there are ways to pocket all the interest you earn. And if your cash savings are bulging right now, it might be worth weighing up whether your money is being put to best use.

Why are more savers paying tax?

The two factors at play here are higher interest rates and frozen tax allowances.

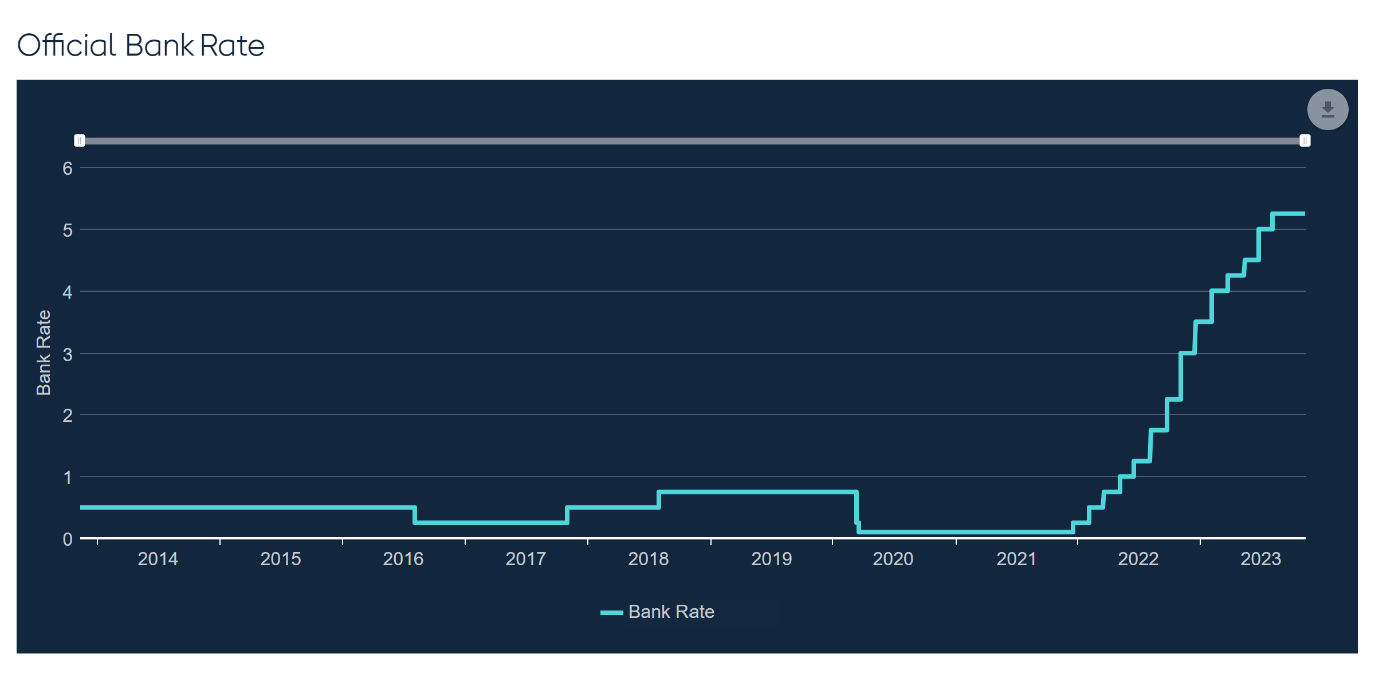

After years in the doldrums, interest rates rocketed from 0.1% to 5.25% between December 2021 and August 2023. The savings rates offered by banks and building societies have followed suit, albeit sometimes sluggishly, jumping above 6% until recently.

In addition, the personal savings allowance, which lets you earn a certain amount of interest before paying tax, hasn’t risen since it was introduced in 2016. This is part of a broader stealth tax grab by the government, known in industry jargon as fiscal drag, where frozen tax allowances pull more people into higher tax brackets.

What’s the savings allowance and how does it work?

If you’re a 20% taxpayer, the first £1,000 you earn in interest every year is tax free, while if you pay 40% tax the allowance halves to £500. Anyone in the 45% tax bracket doesn’t get an allowance – you pay tax on the lot.

As noted above, until recently, interest rates languished at historical lows, reflected by paltry savings rates.

The chart below shows the trajectory of interest rates over the past decade.

Now that interest rates have risen sharply, more people are tripping above the savings allowance, exposing their income to tax.

At the time of writing, the best easy-access savings account pays 5.22%, while if you’re prepared to lock your money away for a year, you can get 5.91%. This means that if you’re a 20% taxpayer, the allowance could be used up once accessible savings hit £19,150 - or £9,575 if you pay 40% tax.

In contrast, in December 2021, before interest rates began their upwards march, the top easy-access account paid just 0.71%. At this rate, a 20% taxpayer could have £140,000 in savings and not breach the personal savings allowance, reducing the need to use tax wrappers.

How can I pay less tax on my cash savings?

Fortunately, there are ways to shield your savings interest from the taxman.

Your first port of call should be to consider using your ISA allowance. You can invest up to £20,000 a year, or £40,000 as a couple, into a Cash ISA and pay no tax on any interest you receive.

I recognise that some of you may prefer to use a Stocks and Shares ISA every year because of the greater potential returns on offer, leaving little-to-no room for your savings.

There are some other things to think about, though. If you’re married or in civil partnership and have both used up your ISA and personal savings allowances, then it might be worth switching the bulk of your cash savings to whoever pays the lowest rate of income tax.

For example, you’re in the 40% tax bracket while your spouse pays 20%, and each have £25,000 in savings at an interest rate of 5%. You will pay £500 in tax (£1,250 x 40%), while your partner’s tax bill will be £250 (£1,250 x 20%) – a total of £750.

But keeping all the money in your partner’s name would reduce the tax payable to £500 (£2,500 x 20%) – a saving of £250.

Premium Bonds are a further option. Instead of earning interest on your money, you’re entered into a monthly prize draw. Prizes range from £25 to £1 million and are tax free, but there’s no guarantee you’ll win. On the plus side, the prize fund rate recently rose to 4.65% - its highest level since 1999.

How much cash should I hold?

If your cash holdings are large enough to absorb your savings allowance, this could be a sign you’re keeping too much.

While cash is more secure, the stock market, despite exposing you to more risk, offers greater potential to grow your wealth over the long term.

How much money you choose to allocate to cash, rather than invest in the stock market, is a personal decision. It typically depends on any short-term plans for the money, your capacity to bear investment losses, and whether you’re retired or still working.

A useful rule of thumb is to keep at least six months’ expenditure in any easy-access savings account, such as a Cash ISA, to cover emergencies, plus extra to fund any immediate goals such as holidays and big-ticket purchases.

- The highest-yielding money market funds to park your cash in

- 10 things to know about money market funds versus cash savings

If you’re retired and using income drawdown, it’s worth keeping two to three years’ income in cash - either inside or outside your SIPP - to avoid encashing shares when prices are low. This will protect you from threats such as sequencing risk, which can occur when you continue to sell stocks when markets fall, which can deplete your retirement funds quicker than planned.

Self-employed workers may also want to keep a larger cash buffer to fall back on should work dry up for any reason - or you suffer an illness or injury that puts you out of action.

How else can I reduce my income tax bill?

-

Use pensions, including salary sacrifice

Paying into a pension is a great way to immediately reduce your income tax bill, as long as you're prepared to lose access to the money until age 55 (rising to 57 from 2028). You can contribute the lower of £60,000 or 100% of earnings (called your annual allowance) every year and get tax relief at your marginal rate – in other words, the top rate of tax you pay, which could save you up to 45%. But if you’re retired or earn more than £260,000 a year, your allowance could drop as low as £10,000.

If you’re employed, a further option is to use salary sacrifice. This is where you trade a portion of your salary for a pension contribution. For example, you earn £60,000 a year and you agree to exchange £3,000 of your salary for a pension payment. Because your earnings drop to £57,000, you will save £1,200 (£3,000 x 40%) in income tax plus £60 (£3,000 x 2%) in national insurance (NI).

What’s more, not only will the £3,000 pension payment escape income tax and NI, but the money will grow free from capital gains tax (CGT), while any dividends you receive are sheltered from the taxman, too.

-

Claim the marriage allowance if you can

Several tax perks are available to those who’ve tied the knot, one of which is the marriage allowance. This allows you to transfer £1,260 of your personal income tax allowance to a spouse or civil partner, which could reduce their tax bill by up to £252. The one sting in the tail is that the higher earner can pocket no more than £50,270 a year,

For instance, let’s say you earn £45,000 a year while your spouse earns £10,000. As your spouse’s income is below the personal income tax threshold of £12,570, they can switch £1,260 to you, beefing up your personal allowance to £13,830.

While this won’t provide a mammoth saving, it can provide some valuable extra cash for little effort.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Editor's Picks